India’s gig economy in the age of AI -Governance Now

The World Economic Forum’s ‘Future of Jobs 2025’ marks a decisive break from the gloom of the pandemic years. It projects that by 2030, advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and automation will create 170 million new jobs and displace 92 million worldwide, yielding a net gain of 78 million roles. Technology and sustainability are now the twin engines of this expansion, with AI, data, green energy, care and education sectors driving most of the growth and reshaping how work is organised across the globe, including in India. For an economy where unemployment has stopped falling and youth joblessness remains high despite rising labour force participation, this is both an opportunity and a warning.

A Faster AI Wave, A Narrower Skills Window

The 2025 report is both more bullish and more exacting than its 2023 predecessor. It finds that AI and information processing technologies will transform 86% of businesses by 2030, with investment in generative AI rising eightfold since the launch of ChatGPT. World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that 39% of current skill sets will be obsolete between 2025 and 2030, even as AI and automation alone generate 170 million jobs and wipe out 92 million, reshaping tasks across sectors rather than simply adding or subtracting headcounts. The fastest growing skills are AI driven data analysis, networking and cybersecurity, and basic technological literacy, which are fast becoming prerequisites not just in formal employment but also in the platform and gig economy. (The gig economy refers to a labour market where individuals earn income from short term, task based or project based work, often mediated by digital platforms rather than from traditional, permanent employer–employee jobs.)

India’s Labour Market: Plateauing Unemployment, Rising Participation

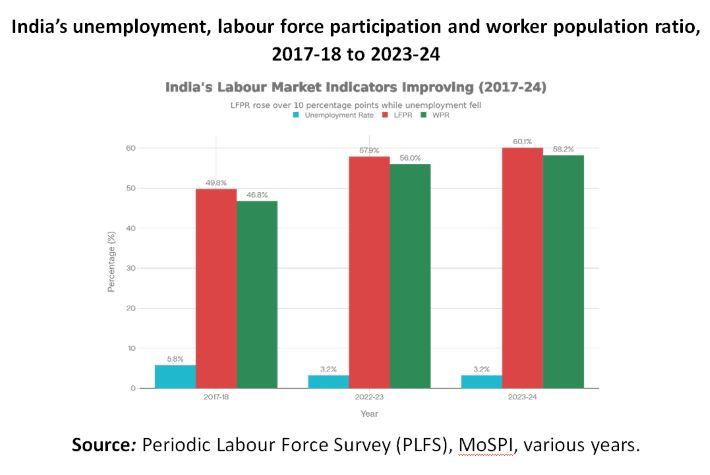

India’s latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data for 2023 24 show headline unemployment stabilising at 3.2%, the first year since 2017 18 without a decline. Beneath that apparent stability, the labour market is deepening: the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) has risen from 57.9% in 2022 23 to 60.1% in 2023 24, with rural LFPR up to 63.7% and urban LFPR to 52%, indicating more people, especially womenentering the labour market. The Worker Population Ratio (WPR) has edged up to 58.2%, but female unemployment has ticked up to 3.2% even as male unemployment has dipped slightly, highlighting persistent gender asymmetries in access to quality work. These developments overlay a longer term story of elevated youth unemployment and a drift away from secure formal employment toward informal work and self employment, including a growing array of gig arrangements documented in PLFS and Economic Survey analyses.

Gig and Platform Work: The New Shock Absorber

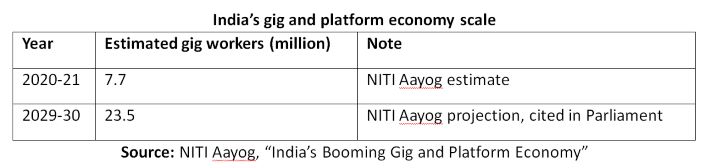

In this context, gig and platform work has become India’s de facto labour shock absorber. NITI Aayog’s widely cited estimates suggest there were about 7.7 million gig workers in 2020 21, a figure projected to rise to 23.5 million by 2029 30, a magnitude broadly endorsed in subsequent replies in Parliament. These workers are clustered in delivery, mobility and home services, alongside a rapidly expanding layer of digital freelancing that intersects directly with WEF’s high growth domains such as e commerce, data enabled business services, AI linked microtasks and online content work. Yet most of them operate with minimal social protection: platforms typically classify workers as independent contractors, placing them outside standard frameworks on minimum wages, working hours, social security and collective bargaining.

The New Constraint: Skills, Not Jobs

‘Future of Jobs 2025’ is unequivocal that the main bottleneck will be skills rather than the number of jobs. Globally, the report warns that nearly four in ten workers will require reskilling by 2030, and that firms increasingly view “skills gaps” as a more binding constraint than macro economic weakness. In India, this is already evident: government briefs and employer surveys point to persistent talent shortages in accounting, finance, IT, 5G, cloud, AI, big data analytics and cybersecurity, even as LFPR rises and large numbers of women and youth remain unemployed or trapped in low productivity roles. WEF’s India focused analysis underscores that realising the benefits of the projected global net job gain depends on closing education and skills gaps, reforming labour regulations and improving the ease of doing business to unlock high productivity employment.

From Precarious Gigs to a Productive Platform Economy

Taken together, India’s PLFS trajectory and the ‘Future of Jobs 2025’ findings point towards a demanding but clear policy agenda. First, the gig and platform economy must be explicitly integrated into the national jobs strategy instead of being treated as an informal side show. This means operationalising the Code on Social Security provisions for gig and platform workers by creating funded mechanisms for health insurance, accident cover and pensions, financed via a small levy on platform revenues and aligned with the national e Shram database.

Second, skilling efforts need to pivot from generic short term courses to defined pathways into WEF identified growth areas like AI support roles, cybersecurity, cloud operations, digital marketing and green services with a deliberate focus on women, rural youth and non metro workers who are currently over represented in low end gig work. India’s position as one of the main suppliers of the future global workforce alongside Sub Saharan Africa, contributing nearly two thirds of new labour force entrants, will otherwise be undermined by its own skills deficit.

Third, labour market data systems such as PLFS, the Quarterly Employment Survey (QES) and administrative registers must begin to track platform work explicitly, so that rising LFPR and stable unemployment rates do not conceal a silent shift toward unregulated, low wage flexibility. For markets, that would distort signals; for policymakers, it would mean celebrating “job creation” while ignoring erosion in job quality.

‘Future of Jobs 2025’ offers a rare piece of good news: even in an AI intensive world, more jobs could be created than destroyed by 2030. Whether India rides this global upswing or is overwhelmed by it will depend less on headline job numbers and more on the composition of employment-formal versus informal, protected versus precarious, exclusionary versus genuinely inclusive. The gig economy sits precisely on that fault line. Economic policy now has to decide whether it remains a buffer of last resort, or becomes a platform for the next generation of productive, technology enabled work.

Dr. Vani Archana is a Senior Fellow, Pahle India Foundation.