Solving India’s Employment Paradox for Long-Term Development

Image Source: Getty Images

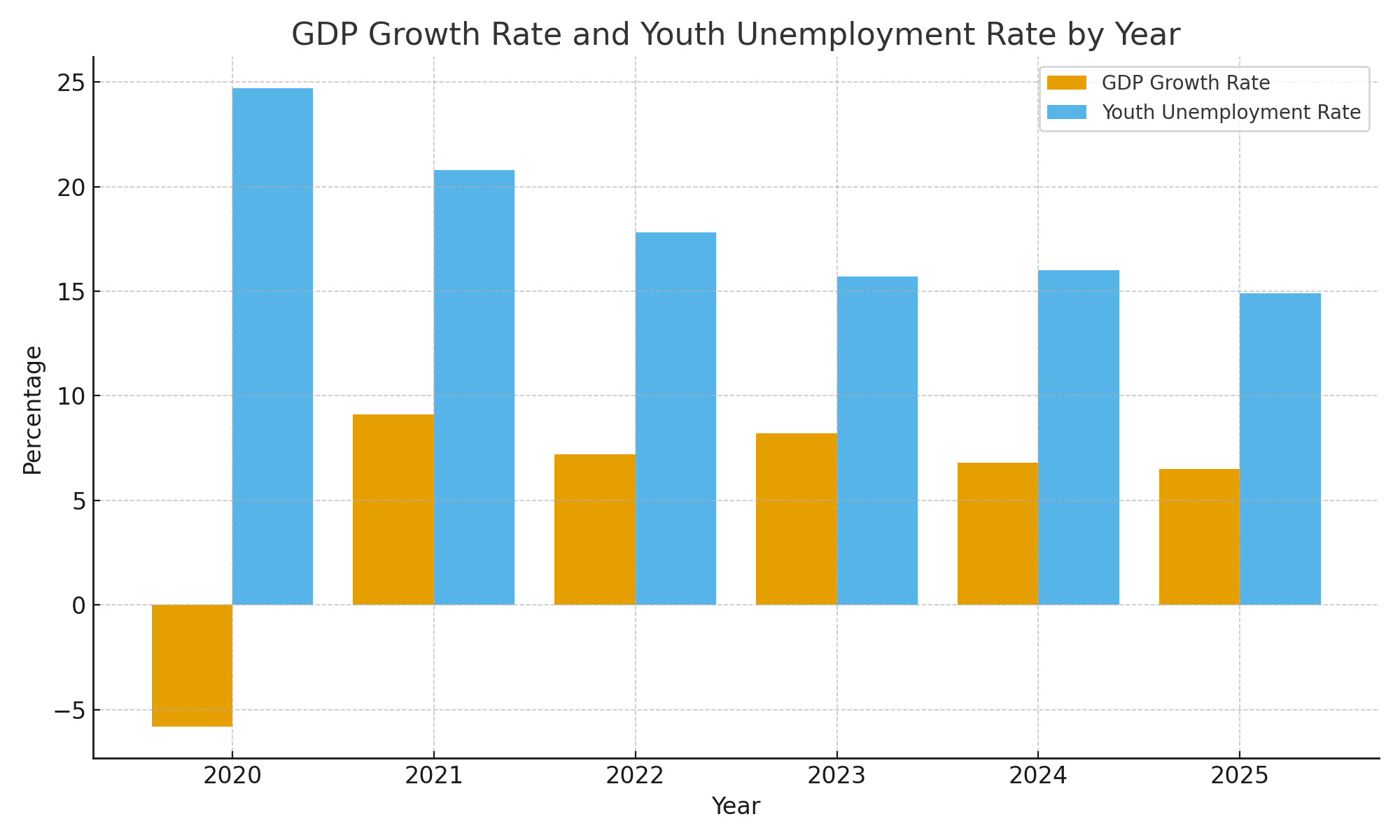

In 2025, India presents a stark economic paradox. As it cements its position as the world’s fastest-growing major economy with Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates consistently north of 7 percent, the national discourse, somewhat paradoxically, seems centred around another distasteful reality: the chronic unemployment crisis. For the millions of educated and aspirational young Indians who are either unemployed or underemployed, the celebration of macroeconomics will be a hollow one. Not merely a statistical oddity, this disconnect between headline growth and actual job creation at the ground level constitutes one of the most crucial challenges to India’s long-run development, societal balance, and global competitiveness. The extent of this problem is enormous: each year, over 12 million young people pour into the Indian labour force, a demographic wave with the potential to be a dividend. However, this is now turning into a source of extreme disillusionment. Recent data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) and the government’s own Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) have consistently highlighted a picture of increasingly high unemployment rates, especially a worrying concentration of that among the youth and educated ones. This shows that it is not just about jobs but an egregious mismatch between the demand and supply of labour.

Figure 1: The widening gap between GDP and youth unemployment

Sources 1: Trading Economics; PIB Press Release; AngelOne

To craft an effective solution, we must first dissect the multifaceted causes of this employment crisis. Four key structural issues stand out:

1. The Double-Edged Sword of Automation: The Fourth Industrial Revolution is no longer a distant threat. Automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are changing industries that once served as engines for creating good jobs. While some new high-skill jobs have been created in fields such as data science and machine learning, they still lag behind the plateauing opportunities in IT services, back-office processing, and even manufacturing. Furthermore, the rate of job loss in lower-skilled occupations is generally accelerating faster than job creation and high-skilled occupations, leaving a large number of displaced workers behind, and worsening inequality.

2. A Stagnant Manufacturing Sector: India has struggled to execute the classic development model of moving labour from agriculture to job-intensive manufacturing, a path successfully trodden by East Asian economies. To understand the scale of the missed opportunity, one needs only look to the region’s history. South Korea rapidly industrialised by adopting Export-Oriented Industrialisation in the 1960s, prioritising labour-intensive exports before moving up the value chain. Taiwan leveraged a unique model of SME-led Export Clusters, integrating nimble small enterprises into global supply chains through government-supported industrial parks. Similarly, China successfully mobilised its massive rural surplus labour through Township and Village Enterprises (TVEs), which brought manufacturing directly to the countryside rather than forcing migration to cities. In the 1980s, Vietnam unlocked its manufacturing potential through the Doi Moi reforms, shifting from central planning to a market-oriented, export-led model that welcomed foreign investment. Despite flagship initiatives including ‘Make in India‘ and the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes, the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP and, more importantly, employment, has remained stubbornly low. The focus has often been on capital-intensive industries such as electronics and automotive assembly, which, while valuable, do not create the mass employment needed to absorb the influx of new workers. The ecosystem to support low-skill, labour-intensive manufacturing, such as textiles, footwear, and food processing, remains underdeveloped compared to competitors like Vietnam and Bangladesh.

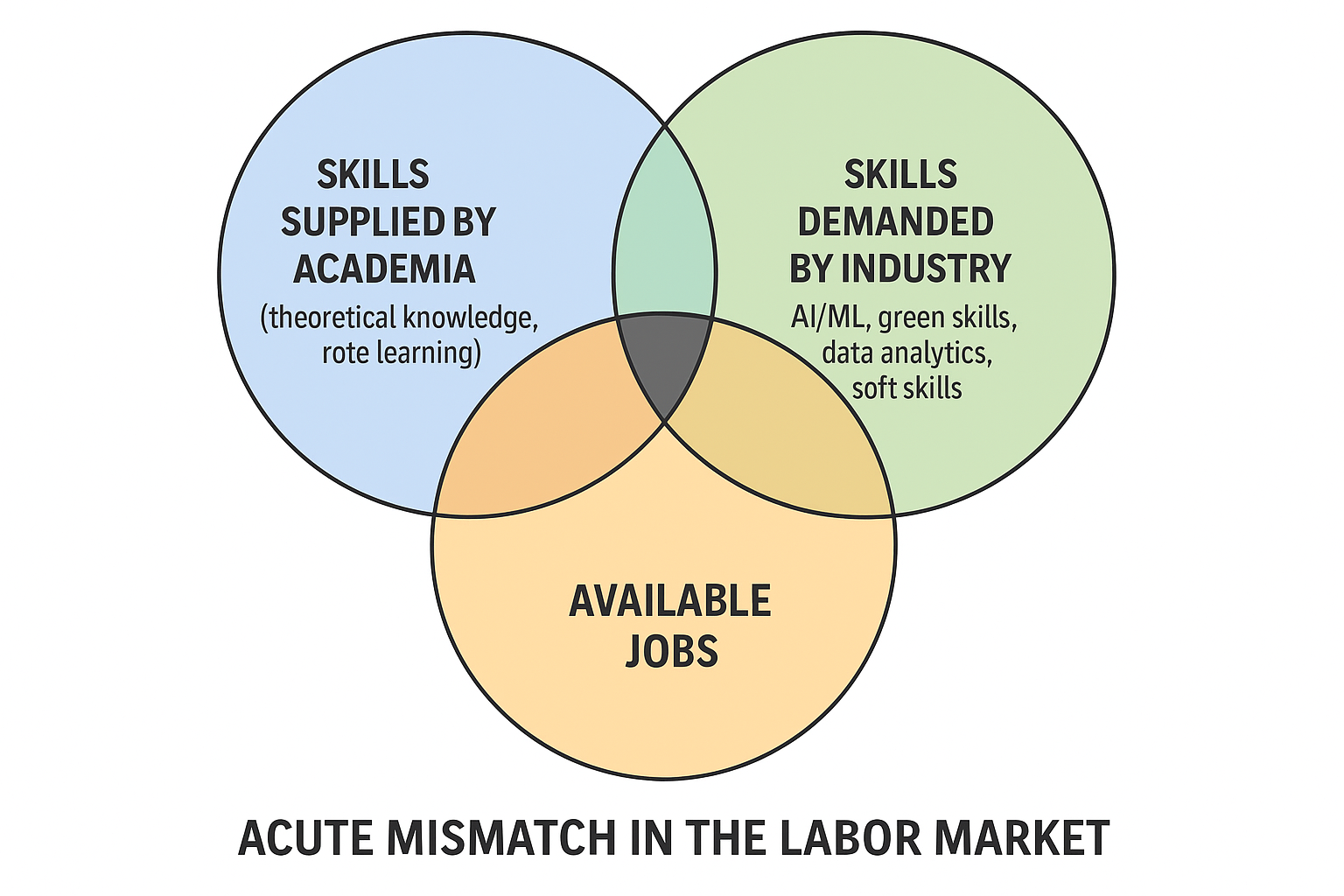

3. The Pervasive Skill Mismatch: India’s education system, despite its scale, is failing to produce job-ready graduates. A curriculum rooted in rote learning and theoretical knowledge leaves students ill-equipped for the demands of a modern economy. A recent NASSCOM report highlighted the significant gap between the skills industry demands—such as critical thinking, data analytics, and green-tech expertise—and the skills possessed by the graduate pool. This results in a frustrating situation where industries complain of a talent shortage even as millions of graduates remain unemployed.

Figure 2: The skill opportunity chasm

Sources 2: India Skills Report

4. The Precariousness of the Informal Sector: The informal economy, which employs nearly 90 percent of India’s workforce, serves as a default shock absorber. However, it is a sponge that offers precarity and not prosperity. Jobs in this sector are characterised by low wages, a lack of social security, and poor working conditions. While essential for subsistence, the informal sector cannot provide the stable, upwardly mobile employment that a modern, aspirational India demands. Efforts at formalisation are slow and have yet to address the core vulnerabilities of these workers.

Addressing this crisis requires a fundamental reorientation of India’s economic policy. The goal must shift from simply growing the economy to growing the economy inclusively. This demands a multi-pronged approach:

The challenge is immense, but so is the opportunity. The same demographic force that threatens instability could power India’s rise as a global economic leader for decades to come. However, this dividend will not be realised automatically. It requires a decisive policy shift that places job creation and human capital development at the very heart of India’s growth story. GDP growth without job growth is ultimately unsustainable, and it is time for India’s development narrative to reflect this foundational truth.

Hamza Ahmad is a Research Intern at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.